My friend Tim Sundles who owns Buffalo Bore ammunition has become quite the YouTube sensation. Not too long ago Tim and his lovely wife started a YouTube channel and have already amassed nearly twenty thousand subscribers. I’d suggest you check out the Buffalo Bore Ammunition & Buffalo Bore Outdoors YouTube page, partly because its refreshing to hear someone speak about guns and related topics without a sponsor driven agenda, but also partly because Tim provides practical information, and you might learn something. I wish them well in their endeavor and hope YouTube treats them better than they treated me.

YouTube removed my channel permanently.

The point of this post is to discuss one of Tim’s recent videos where he talks about kinetic energy and how it relates to effectiveness on large animals. (I’ve been looking for a reason to dive into this topic.) As Tim states in the video, most of the gun industry would have you believe there’s a direct correlation between foot-pounds of energy and lethality. Tim insists there’s not and uses an example of a 45-70 shooting a 405-grain bullet at 1350 fps and a 22-250 shooting a 50-grain bullet at 3800 fps. Both generate an almost identical amount of kinetic energy, and, because it’s a comparison even novice hunters can relate to, it’s a greet illustration of the confusion around kinetic energy and lethality.

Energy is the capacity for work and kinetic relates to motion. So, kinetic energy is energy from motion, or as defined by Britannica, “is a form of energy that an object or a particle has by reason of its motion.” You can calculate the kinetic energy for a bullet in foot pounds using the formula: m*v2, where m = the bullet weight in grains and v = the bullet velocity in feet-per-second (fps). When you’re working with fps and grains, you must divide the product by 450,400 to represent foot-pounds. When we say a bullet has 1600 foot pounds at a certain velocity, we are representing the amount of work the bullet could conceivably do at that speed.

In Tim’s 45-70 and 22-250 comparison, even though both bullets have the same foot-pounds of energy at the muzzle, they clearly will not cause the same effect when they hit an animal. Foot-pounds of energy is very similar to horsepower with automobiles. A 4x4 truck and a sports car can both have the same amount of horsepower, but the work they’re capable of is very different. For example, the truck could pull the sports car out of a mud hole, but the sports car can outrun the 4x4 truck. The difference in the work these two automobiles can do with that 300 horsepower exists because of transmissions, gear boxes, differentials, and tires.

The same is true with the 45-70 and 22-250 comparison. Think of one as the truck and the other as the sports car. A bullet’s weight, combined with how it’s designed to react to impact, magnified by velocity, determines the work it can do. Velocity is critical because a motionless bullet is harmless, unless maybe you step on it with a bare foot. Because of its slow velocity the 45-70 bullet will maybe slightly deform and penetrate very deep, poking holes in a lot of important things. On the other hand, the 22-250 bullet — most, not all — will seemingly explode and create a shallow but nasty wound that may very well not reach the vitals of a big game animal. Both bullets do the same amount of work based on kinetic energy, they just do it differently.

I’m sure you’ve seen Newton’s cradle, which is a device with several suspended metal balls. If you pull a ball on one end back and release it, it impacts the remaining balls and the ball at the opposite end moves. That is an example of energy transfer. When a bullet impacts something, it transfers some of its energy to what it hits, and this destructive energy is what damages living tissue. But a bullet also creates thermal and sound energy; they get hot when fired and make noise when they impact. When most hunters think of kinetic energy, they mistakenly only consider the size and depth of the hole a bullet makes inside an animal. However, impact transforms some of the kinetic energy into mechanical energy that’s used to upset/deform – or as some like to call it, expand – the bullet. For example, when a bullet impacts a steel plate, it transfers some energy, creates heat, and makes noise, but most of its energy flattens the bullet.

Let’s go back to the 45-70 and 22-250 comparison. The 45-70 bullet did not expend every much energy to deform the bullet. Because of this it did not upset with a wide frontal diameter or lose a lot of weight. This allows the bullet a lot of remaining energy to penetrate. The 22-250 on the other hand used a substantial amount of its available energy to deform/fragment the bullet.

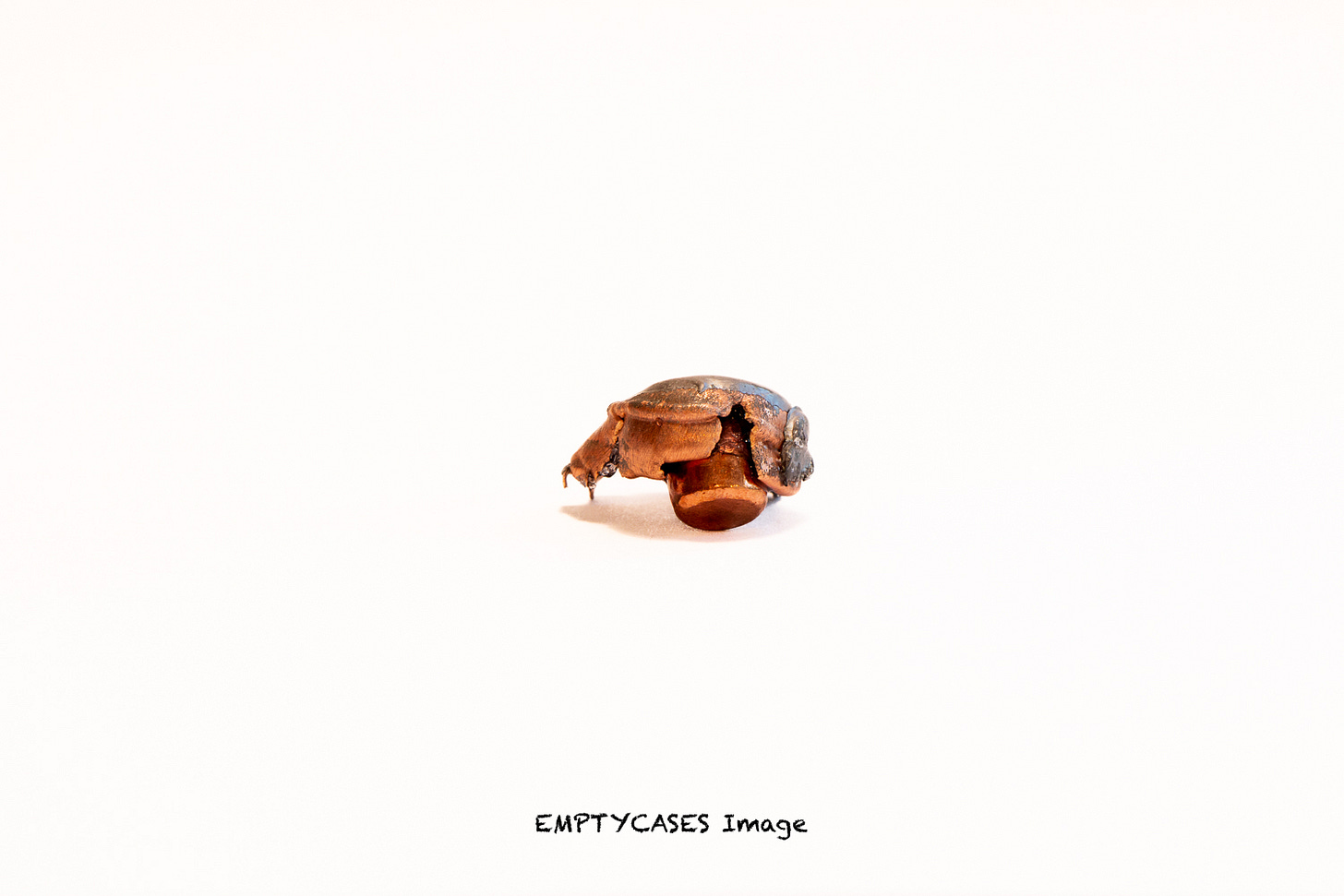

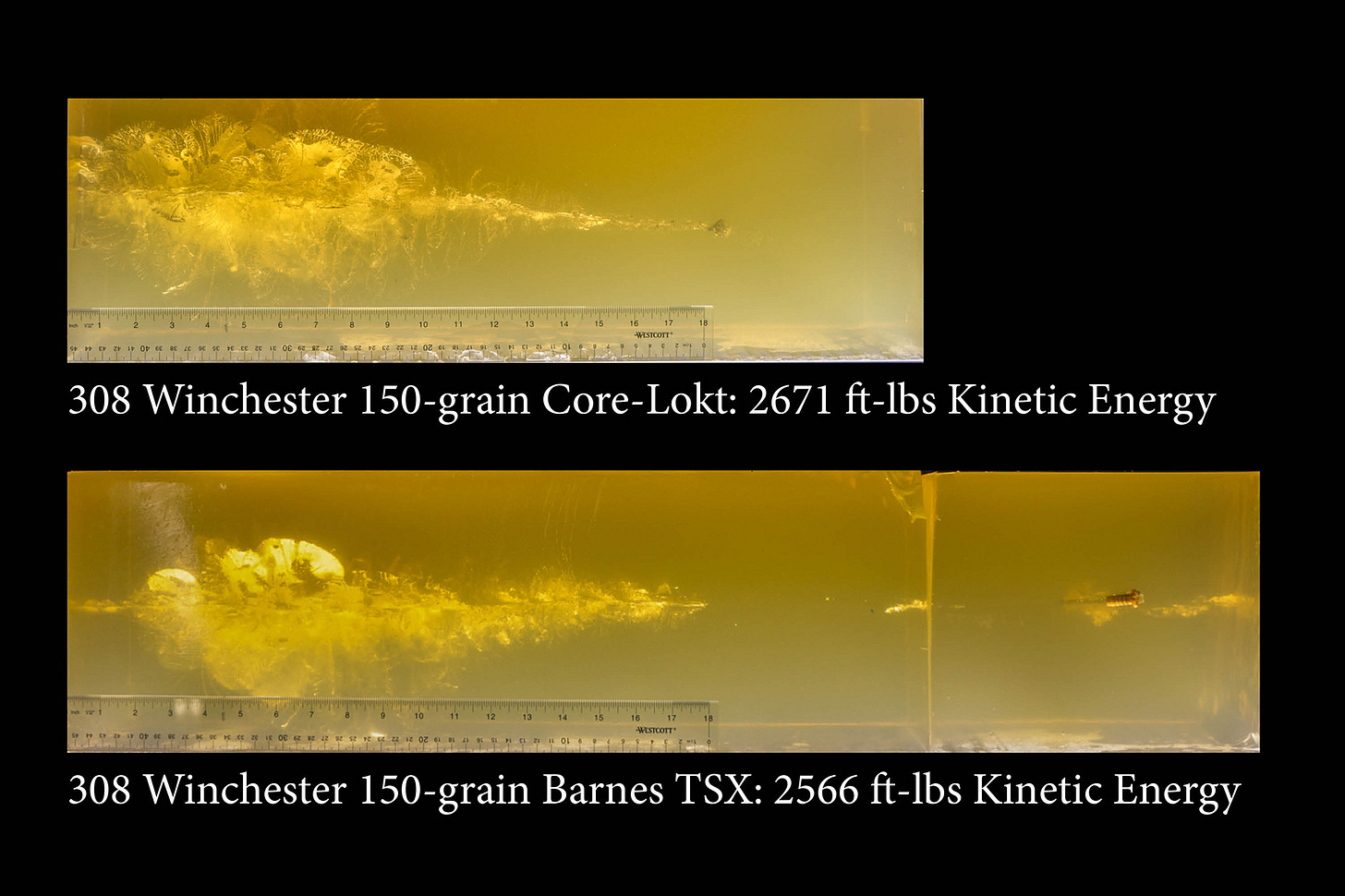

I conducted an experiment a few years back to see how much kinetic energy bullets lose after penetrating six inches of 10% ordnance gelatin. What we found was that mono-metal bullets like the Barnes TSX will lose about 50% of their kinetic energy through that medium. However, cup and core bullets like the Remington Core-Lokt can lose as much as 85% of their energy. The harder mono-metal bullet resists deformation and upset to a point, conserving kinetic energy – velocity and weight – for penetration. The kinetic energy chews up the Core-Lokt bullet and through a combination of its loss of weight and lack of remaining velocity – kinetic energy – it does not penetrate very well. Its not that one is bad and the other is good, its that they are designed to work differently.

Below are the results from three bullets that clearly shows how bullets react to or use the kinetic energy in different ways. The bullet with the most kinetic energy did not penetrate the deepest, and the bullet with the least kinetic energy penetrated deeper than the one with the most. It’s not the kinetic energy as much as how it’s used by the bullet. I’ve taken deer with all three of these loads, and also with a 130-grain hardcast BuffaloBore load for the 327 Federal Magnum out of a revolver that impacted with less than 400 foot-pounds of kinetic energy. All those deer fell over dead in almost identical fashion. Kinetic energy did not kill those deer, but the way the energy was used, did.

Kinetic energy is just horsepower, bullet construction is the transmission and gear box, and it’s all driven by velocity. This is an oversimplification of something that is very complex. It is a conundrum bullet an ammunition manufacturers are continually working to perfect, through the development of new bullets and even new cartridges. Their goal is to maximize the use of the available kinetic energy to serve certain purposes. By tweaking bullet weight, bullet design, and velocity, they manipulate the kinetic energy – horsepower – to do the work they want done in a specific way. Even high ballistic coefficient bullets are an example of this tuning. They conserve velocity and energy to fly flatter and hit harder at distance.

So, is kinetic energy important? Yes, it’s a reflection of power. Does it corelate to a bullet’s effectiveness on animals. Yes, but only when tempered by how the energy is used. The more kinetic energy a bullet has, the more work it can do. But bullets work in very different and sometimes even mysterious ways. As Tim perfectly illustrated with his 22-250 and 45-70 comparison, kinetic energy alone will not tell you how effective your cartridge/load/bullet combination will be at killing something. Just as Tim also explains, bullet construction is very important, and it is the gremlin that nullifies every so-called killing power formula based on bullet weight, caliber, and velocity that hunters like to trust, swear by, and argue about.

I’ll finish all this with a quote from Finn Aagaard about killing power formulas. Finn was an African professional hunter and one of the best gun writers to ever pound a typewriter. Finn once wrote, “Rather than relying on fanciful “killing power” formulas, hunters would do far better to learn field marksmanship and to make some study of animal anatomy, in which subject most of them, including most outdoor writers, are woefully deficient.”

That's a great book, though I think it overcomplicates shot placement. https://emptycases.substack.com/p/shot-placement

I have watched Tim’s entire volume of YouTube content and enjoyed it. His observations on what works in the field is from actual hunting, and killing experience.

The comment and quote about Finn the professional hunter is appreciated. For good training, my preferred venue is Gunsite. For the study of game animal anatomy I like the book “The Perfect Shot” by Dr. Kevin Robertson.