I’ve been fortunate to have hunted a lot of different animals in a lot of different places. I could be mostly content to spend the rest of my life hunting in West Virginia for whitetail deer, because I enjoy that hunting more than any other kind. I also relish hunting kudu, but like with whitetail deer – oddly – I really only want to hunt them in one location, which is in Africa’s Northern Cape on a friend’s farm. The one animal I have not hunted, that I most want to hunt, is lion.

It is not so much a desire to kill a lion, I want to hunt the lion. There are however complications to this desire or dream. I would only want to hunt a lion with professional hunter Geoffrey Wayland because of the trust I have in him, the hunting history we have together, and the friendship we share. There are other complications too, which I’ll address shortly.

Because of this burning desire or aching dream to hunt lions, I’ve spent a lot of time reading about lion hunting. But not about modern day commercialized lion hunting, about lion hunting back in the day when it was more of, man verses lion in the wilds of Africa, without a professional looking over his shoulder telling him what to do and providing protection.

One of the most interesting works is The Book of the Lion (C. Scribner's Sons. 1914), written by Sir Alfred Edward Pease. In the passage below Pease talks about his preferred weapon for lion hunting.

“As to rifles, I prefer to have one light handy rifle and a double-barrelled ball and shot gun carried in reserve, when after lions. The rifle which has been my constant companion since 1892 is a rather short barrelled, five shot magazine -256 Mannlicher; any apparent deficiency in size of bore and weight of bullet is compensated for, in my opinion, by the ease and rapidity with which it can be manipulated, the little room occupied by ammunition, the flatness of the trajectory and the superiority of its striking energy over some of the larger bores. With the "256 I have killed many lions as well as pachyderms, and antelopes from greater kudu downwards, it is no weight to carry on foot or on horseback, and the mechanism is of the simplest and strongest kind; wet, sand, mud, tumbles, and croppers have never injured it, and a soft-nosed bullet or a ratchet H.P.1 Fraser's ball "sets up" so well that at times it makes a hole almost as big as one of nearly double its calibre.”

256 Mannlicher is the English designation for the 6.5x53mmR, which is ballistically nearly identical to the 6.5 Creedmoor or 260 Remington. This is not a rifle many would consider suitable for lion. But lions are not difficult to kill. Wally Johnson was a professional hunter in Africa some years after Pease’s experiences, and Johnson killed a passel of lions with a 30-30 Winchester. As quoted in his biography, The Last Ivory Hunter: The Saga of Wally Johnson (St. Martin's Publishing Group, 1988), Johnson said, “I killed something like thirty to forty lions with that .30-30, and now that the years have sifted by, I realize what a wonder it is that I’m still around to tell my tale.”

There is of course a difference in a killing rifle and a stopping rifle. Lots of dangerous African game has been killed with the 256 Mannlicher, the 7x57 Mauser, and the 303 British. Undoubtedly, these animals could still be killed, and in better fashion, with these same cartridges today, especially with the better bullets we now have. But they are not stopping cartridges designed to pulverize dangerous creatures hell bent on stomping you into a blood puddle or ripping your lungs out. As noted, Pease had a, “…a double-barrelled ball and shot gun carried in reserve,…” As my friend Tim Sundles just recently proved on his farm down in Africa’s Eastern Cape, sometimes big guns are the right guns. You can see his VIDEO on YOUTUBE, it is not available to share here because its age restricted.

And of course, now, hunting regulations often stipulate the gun/cartridge necessary for lion hunting. I firmly believe a 140-grain Fusion bullet from a 6.5 PRC placed properly would quickly kill a lion, and maybe even stop one. However, as much as I would like to tackle a lion with the same caliber rifle used by Pease, I believe a 375 H&H might be mandated and that a 45-70 would be more fun. Ultimately, I’d be happy hunting with a wide array of hunting cartridges, if Geoffrey was with me, and if he was armed with his battered, proven, and trusted, 375.

Another very interesting read is the book, The Rediscovered Country (1915) written by Stewart Edward White. White wrote the below passage after what might best be described as a gun battle with several lions. White hit one lion three times, with the last shot delivered at eight paces. He hit one of the other lions four times, another lion twice, and the largest lion seven times. White used two rifles during this engagement – a 405 Winchester and a Springfield. But maybe most amazingly, his gun bearer stood behind him, faithfully and fearlessly, alternately reloading White’s two rifles and handing them to White as the fight wore on.

"This is, in my opinion, the supreme moment in a hunter's life, the moment when, all preliminaries at an end, the lion makes his direct and deadly attack. The little unessentials are brushed aside. Only remains the big primitive idea to fill all a man's mind—kill or be killed. The preliminary maneuverings have made him nervous and jumpy enough to scream aloud; but now all his faculties fall into battle array. He becomes deadly cool. Each of the few movements necessary to bring his weapon into play he executes with what seems to him an almost deliberate precision. A smoldering, repressed emotion fills all his being; it is not exactly anger, but something like it, rather a feeling of antagonism, a pitting of forces and skills. He delivers each shot with an impact of nervous force behind it, as though he were to strike with his own hands. "Take that!" his mind seems to itself to mutter; though of course he has really no time nor attention to waste on articulation. And beneath all this is a great wary alertness that sits like a captain in a conning tower, spying cannily over all the situation as it develops, poised ready to plan competently for the unexpected."

“Excited in the usual sense of the word? No. But alive to the uttermost of all his faculties at once? Yes. That is why the moment is supreme.”

It’s hard to read this an not imagine or dream of a similar experience. I stumbled across the writings of Stewart Edward White when I was researching my book, The Scout Rifle Study (Shadowland Publishing, 2018), because he was a man – a rifleman – Jeff Cooper seemed to highly regard. Theodore Roosevelt felt White was, “the best man with both pistol and rifle who ever shot.” Interestingly, White was what you might call an odd duck. Later, White and his wife authored numerous books divined through what they described as channeling with spirits.

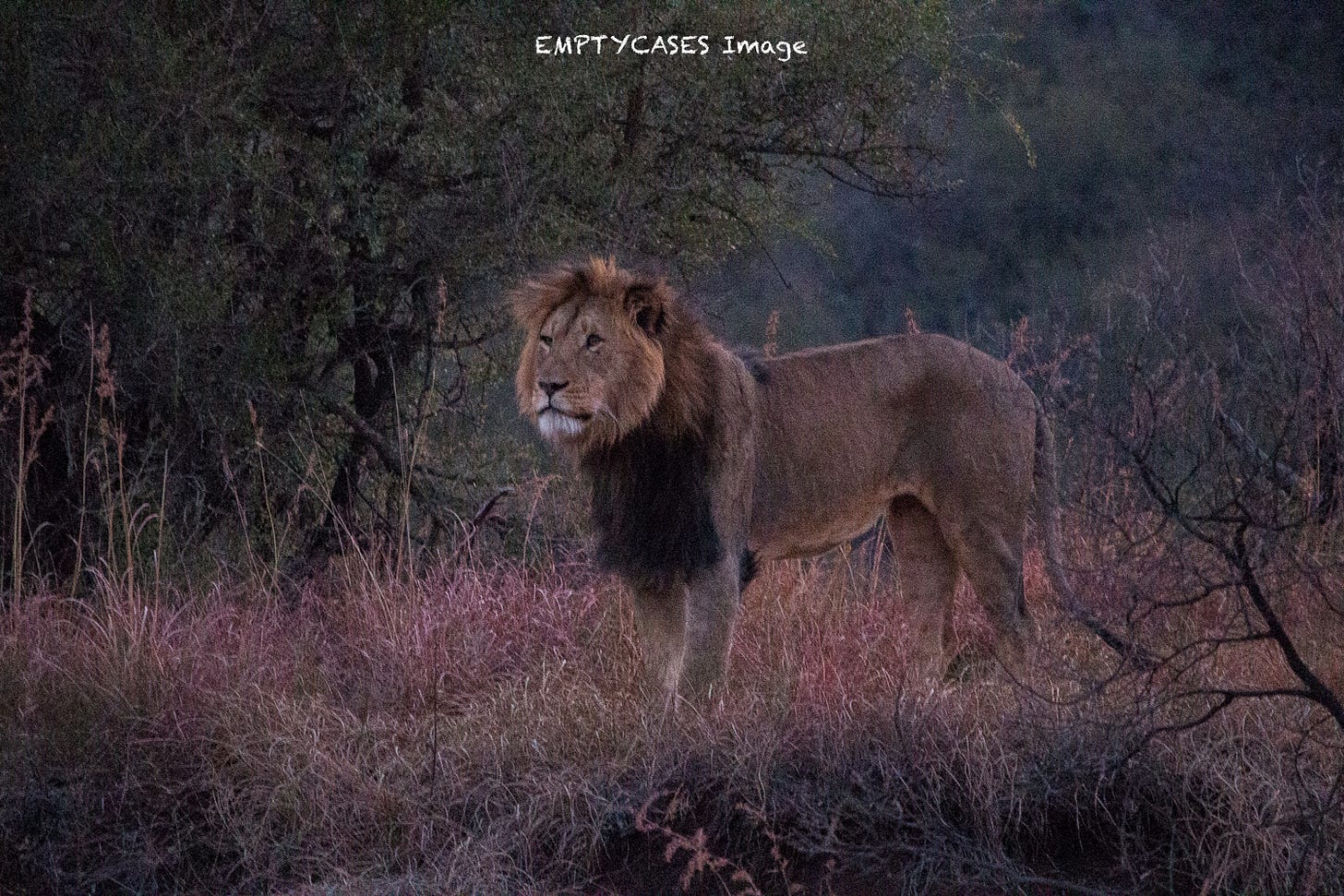

My first up close exposure to lions was inside a large breeding enclosure in the Limpopo Province. The professional hunter I was with took me inside and we drove around looking for the lions. When we found them, the females came right up to the truck and lounged – obviously waiting for food. Finally, a big male made an appearance, but he stayed far back in the bush, watching us intently with a condescending gaze that seemed to say, “Get out of the truck, human. Get out and I will rip your lungs from your chest.”

One female had several cubs, and they too stayed in the bush. Another female just collapsed like she was going to take a nap right in front of us. I had my window down and several of the lions were only feet away. Suddenly, the female in front of the truck sprung to her feet and emitted an ominous growl while looking me dead in the eye. For a brief and chilling moment, my blood turned ice cold as I envisioned her dragging me out of the truck window, just to gain favor with the big male who continued to stare at us with disdain.

That night, alone in my bungalow about a quarter mile away, on my bunk in total darkness, I listened to the lions roar. Nothing I have heard in nature can compare to the nerve twisting, gut wrenching, thunderous earthquake-like sounds lions can make. It does not sound the same as it does on television, because a television and even modern sound systems cannot carry the vibratory sound waves in the same manner that nature can. It is ominously and utterly primeval, and it inspired a now two decade old dream that will not abide.

On occasion in the past, manufacturers have orchestrated hunts for African dangerous game including lion. But lion hunting has become sort of a political football, and it has also become damned expensive. (A free-ranging lion hunt costs about the same as a new pickup truck.) Too expensive for even the largest manufacturer to fund, and too political for them to risk a beatdown on social media. For a gun and outdoor writer with a family to tend, a lion hunt is — financially — out of question. So, unfortunately, I doubt I will ever hunt a lion. And Whiskey, my Rhodesian Ridgeback, is getting too old and fat to be much help, anyway.

But dreams – though unattainable as they might be – are good things to have because when the dreams leave us, life is soon to follow.

More about lions, but not about Hunting

Two other tidbits of lion lore you may find interesting involve World War I and a small riverside community in West Virginia.

About an hour from my home along the banks of the Greenbrier River you’ll find the town of Alderson, West Virginia. In 1890, when French’s Great Railroad Show passed through the town, a lioness gave birth to five cubs. The wife of a local blacksmith adopted one of the cubs and named it “French.” French was docile and friendly, and would take leisurely strolls through town. He was sort of the town mascot, but one day French caused a traveling salesman to have a conversation with God. This resulted in a city ordinance – that still exists – stating no lions were allowed to roam free and unleashed. French was sold to the National Zoological Park in Washington, D.C. Today, throughout Alderson — population 932 — you’ll find various lion statues, and in 2017 a metal sculpture was commissioned. You can drive right by this lion, deep in the Allegheny Mountains, where is stands on the banks of the Greenbrier River.

In another nod to France, a group of Americans volunteered to fly for the French as fighter pilots during the first World War. Their squadron was called the Lafayette Escadrille, in honor of French nobleman, Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, who fought on American soil, for the American colonists, against the British during the Revolutionary War. These brave American’s had two pet lions named Whiskey and Soda, and they served sort of as the mascots for the squadron. Whiskey and Soda were especially attached to Raoul Lufbery, the leading ace of the Squadron, but unfortunately, after eating one of the captain’s expensive hats, the lions were donated to the Paris Zoo.

Originally published in the First Edition of, Under Orion (Shadowland Publishing, 2015), I have included this story because of its relevance to lion hunting.

Lion

“I want to hunt lion.” I said.

“I didn’t think you could do that anymore. Is that still possible?” Dave asked with eyebrows raised.

“I don’t know. It doesn’t matter. I still want to hunt a lion.”

“Why lion?”

“Because.”

Dave wadded up the plastic baggie his sandwich had been in, and then wiped at his beard leaving some mayonnaise stuck to the red hairs, and looked off into the woods at nothing in particular.

“It must be expensive, if you can do it at all.” He wiped at his beard again. “Maybe you could hunt mountain lion instead.”

“No.”

“Is it the danger that entices you? If you shoot well, there should be no danger.”

“No. I have done many things more dangerous.”

“What about big bears? Grizzly and browns? Still expensive, but doable.”

“A bear is not a lion.”

“Or buffalo?”

“No.”

“Well, why? Not that you need a reason but I’m curious.”

“Because he is a lion and there is nothing else like him.”

“Surely it would cost a fortune and then you may not even take one.”

“It doesn’t matter. I want to hunt him, and I want him to know that I am hunting him. And you do need a reason, or it should not be done.”

“Well, yes, I agree, but aside from the hunting reason was what I was curious about.”

“No. The hunting reason is the only reason.”

Dave stood and picked up his pack and rifle. The mayonnaise was still in his beard.

“I have read that they can charge unprovoked, if spooked up close. Or when wounded. I guess that’s lure enough. True excitement I imagine. It must be…”

“I have been charged by animals before. Animals armed with more than teeth. I don’t want a lion to charge me. I want to hunt him.”

Shouldering his rifle and taking a step or two up the mountain, Dave stopped and stared up the slope for a long time. He then turned and looked back at me, undoubtedly wishing he could conjure up a lion for me, right then and there.

“Well, in the end all hunting is the same. A search for something. Doesn’t have to be an animal. It is effort expended to fulfill one or more of the senses.”

“Or all of them.” I said.

Dave looked back up the mountain and then turned to me again.

“Yeah, well. There’s plenty of daylight left and it is a good day to hunt.” Dave sighed. “Let’s imagine we are hunting lion.”

“No Dave. You can not pretend to hunt lion.”

Check out the new section of the EmptyCases Substack called Dispatches, where you can read short notes and observations I’ve made while on the range and in the field.

Thanks!

Nicely written. Chase those dreams!