I’ve seen a lot of articles in magazines and on-line about why you missed your deer, and I’ve even written a few of those. A topic that’s not covered as often is why you might have wounded your deer. Rifle season is approaching here in West Virginia and last year my daughter wounded a nice buck, probably because I’d failed to school her properly. That’s another story and you can read it through the link below. What I want you to think about is that sometimes your point of aim should not be the exact best spot for your bullet to pass through the deer.

Let me preface all this with two facts:

1. A bullet placed through the heart, or at the top of the heart where all the plumbing connects, is the best place for a bullet to go. The heart is the animal’s engine, when you poke holes in it, oil lights come on and animals die fast.

2. No matter how much of a rifleman you are, or think you might be, rarely does your bullet impact at the exact spot you’re aiming. The deer moves at the last moment, or you slightly flinch or snatch the trigger, and the bullet strikes close to – but not exactly on – the spot you’re aiming at.

The problem comes when you try to aim at the exact center of the heart and your bullet hits the deer a bit off mark. If it hits a bit high or a tad back, it’s not much of a problem, you’ve still made a good shot. If it hits a bit low or forward, you could have a long day ahead of you. I’ve written about shot placement before and have strong opinions on the subject. (Click the link below to read about shot placement.) But I also temper my point of aim based on how steady I feel when I’m making the shot, and the angle the animal has presented me. Let’s see if I can use a few diagrams to illustrate this.

Before we get into the weeds on this topic let’s first talk about shot elevation — how low or high you aim on the body of an animal, regardless of the shot angle. I believe the optimum elevation is about 1/3rd of the way up the body and when I’m rock steady that’s my guiding principle. However, I’m rarely rock steady, and when I’m not, to give myself the most margin of error, I tend to aim a bit higher. This prevents a shot I might pull low, from being too low.

Disclaimer: The following diagrams do not represent exact proportions or the exact locations of internal organs. They’re only offered as a guide. Feel free to bitch and moan about any inconsistencies, just keep it to yourself. I’m not trying to educate veterinarians on animal anatomy, these are just representative illustrations to help you aim and maximize your margin of error.

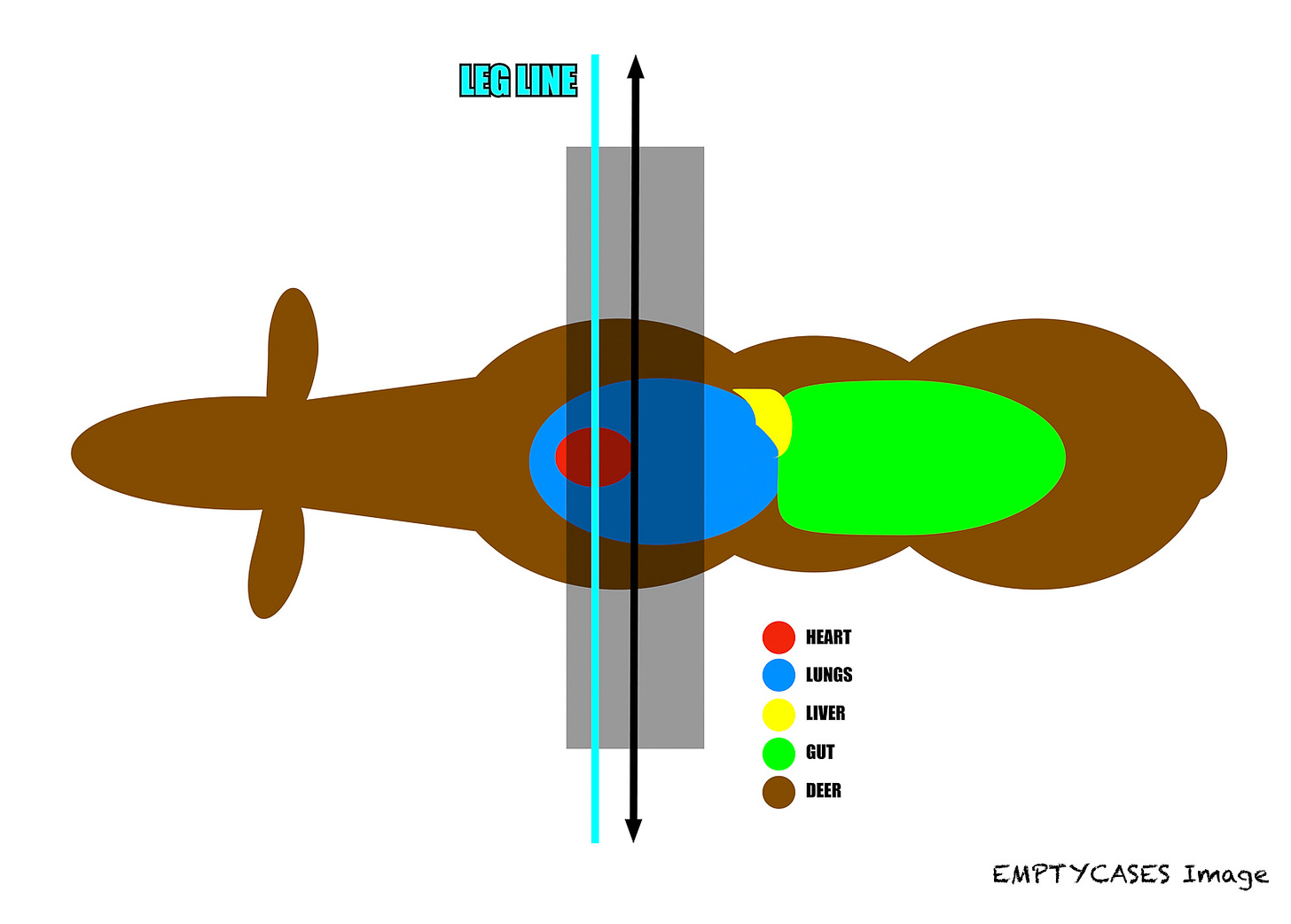

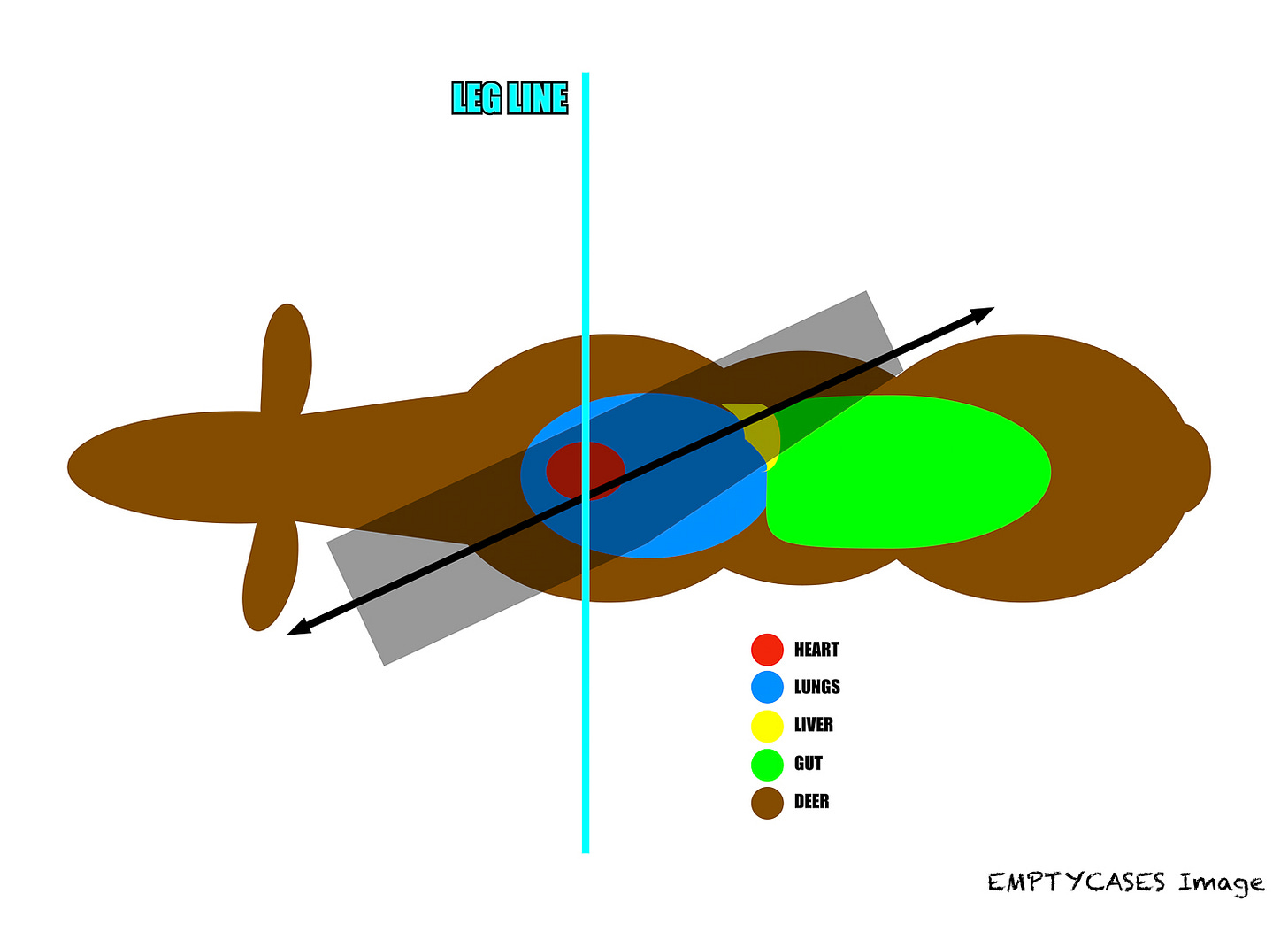

Diagram Explanation: The following diagrams show a deer’s body and internal organ locations from above. Note the cyan colored leg line, which represents the deer’s front legs. The black line represents your point of aim/bullet path, and the partially transparent grey area represents about a six-inch margin of error.

Broadside Shot

Now let’s look at the ideal point of aim – when you’re less than perfectly steady – on a broadside shot. If you aim at the center of the heart, your margin of error extends forward far enough to allow a shot to miss the heart and miss or only clip the lungs. If you aim a few inches behind the heart – leg line – your margin of error is completely contained within the lungs.

0° to 45° Quartering Shot

With a shot on a deer quartering at between 0° and 45°, nothing really changes, at least regarding where you want the bullet to pass through the centerline of the deer. But of course, your point of aim on the outside of the deer does change. The difficult part here is to do as Finn Aagaard described, and as was detailed in my shot placement article – “imagine that the animal has a grapefruit suspended in the center of its chest,” Finn suggested you imagine this grapefruit “above the front legs” and that will work perfectly if you can place your shot perfectly. However, if you imagine the grapefruit just a few inches behind the leg line, your margin of acceptable error will be greater.

Steep Angle Quartering

As the quartering angle increases, you still aim for that centerline spot that’s several inches behind the leg line, but things get complicated, especially on quartering away shots. Notice in the diagram how on a 60° quartering away shot your margin of acceptable error diminishes on one side. This is because an errant shot too far back will hit the deer’s rear quarter and then pass through the paunch. If the shot is too far off, your bullet will need to pass through more than a foot of meat and gut before it arrives at anything vital. Hell, it may not even reach anything vital.

Yes, gut shots kill deer, but it is a slow agonizing death, and you may not find your deer without the help of someone like Shon Butler of Longspur Tracking. Also, nothing inside a deer is better at stopping a bullet than the paunch. This is why it’s generally not a good idea to take a steep angle quartering away shot unless you’re using an extremely deep penetrating bullet with a lot of ass behind it. Even then things can go badly.

On the other hand, with steep angle quartering-too shots, you don’t have to worry about all that muscle in the ham or that nastiness in the gut. However, the bullet can encounter more bone, and bone can sometimes cause bullets to veer off course, especially on glancing impacts. This is typically not an issue with a good bullet. I’ve done a good bit of testing with bone imbedded in various medias and good bullets tend to easily defeat bone and continue on as you hope they will.

Allowable Margin of Error

There’s a term in shooting called “allowable reticle movement” (ARM). It references the reticle movement you see on the target when you’re aiming. Allowable reticle movement or ARM is the amount of reticle movement you can experience and still get your hit. Generally, ARM equates to about half the target size. For example, if you’re shooting at an eight-inch target, allowable reticle movement would equate to about four inches.

What I’m trying to convey or advocate for, here, is that you work within your allowable margin of error when you’re aiming at a deer or any other big game animal. If you’re rock steady, with no reticle movement, aim exactly where you think your bullet will provide the most lethal shot. However, if you have reticle movement your margin of error becomes very important, and you might need to alter your aim accordingly to maximize it. The correct decision – depending on the shot angle – might be to not shoot at all, especially if your ARM exceeds your allowable margin of error. Sometimes bad shots on game come from bad decisions as opposed to bad shooting.

I hope my buddy Shon gets a lot of work this season recovering deer. Through his BloodTrailZAPP, Shon and his trackers get a lot of business, and they make a lot of hunters happy. I’d suggest you bookmark his website and jot down his number, but I also hope none of you need to bother him. There’s enough other hunters making bad decisions and bad shots to keep him plenty busy.

Good article! Even a heart-shot deer can run a good ways. You're right, taking the top of the heart works very well.